This post is based on my (at the time of writing) ongoing research project about the transmission channels of geopolitical tensions. Stay tuned for the full manuscript 🙂

Incredible identification assumptions: 35th anniversary?

Due to international developments during the last couple of years, the macroeconomic effects of geopolitical developments have become a hot-topic in economics. Yet, most of the literature treats geopolitical risk (GPR) as a one-dimensional phenomena with homogeneous economic effects. Notably, most of the empiric literature employing vector autoregressions (VAR) have used traditional Cholesky factorization to identify geopolitical shocks. Naturally, this assumes that only one type of geopolitical shock with homogeneous economic effects drives the system as well as geopolitical risk indicators being exogenous in respect to the macroeconomy. This is implausible. There are several reasons for this:

- News based indices (which is pretty much all of them) are based on the fraction of geopolitics related news articles in the whole corpus, not the raw number of them. Thus, if e.g. a banking crisis hits, the relative amount of non-geopolitical articles falls by definition.

- Even when geopolitical topics are discussed in the media, they are not always news coverage of current events (see discussion in Alonso-Alvares et. al. 2025). Geopolitical topics can for example get engraved into the cultural narrative; one only has to look at the media landscape in Finland every Independence Day, December 6.

- The assumption of all geopolitical shocks – even when only a particular geographical area is considered – having homogeneous effects is implausible on a priori grounds. For example, on and after the Russian invasion of Georgia in August 8 2008 Brent oil futures fell. On and after the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2024 they rose sharply however. In addition recent literature has started to highlight the importance of considering heterogeneous effects of geopolitical events (see e.g. Anttonen and Lehmus 2025)

- Even if one were to abstract from non-geopolitical events affecting news based indices, assuming geopolitical events to be exogenous in respect to economic events is not as straightforward as one would like. For example, the cash flow from oil directly affects Russia’s ability to finance its war in Ukraine both on the operational and the strategic level.

To illustrate the effects different identification assumption may have, I present some results here. The model is a BVAR with following endogenous variables:

- GPR-index from Bondarenko et. al. (2024) which tracks geopolitical narratives from Russian news sources

- Brent oil futures

- Sanctions Intensity index from afore mentioned Bondarenko et. al. (2024)

- Monthly trend indicator of output for Finland

- Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices for Finland

- Industrial production for Germany

- Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices for Germany

- STOXX50 futures

- Euro area shadow rate by Krippner (2020)

The data ranges from 1998M7 to 2024M3. A constant and 12 lags are included. As priors, a normal-inverse-Wishart and a sum-of-coefficients are imposed. For hyperparameters, overal shrinkage is set to 0.1, cross-lag shrinkage to 2, constant shrinkage to 1000 and shrinkage towards unit-root to 1.

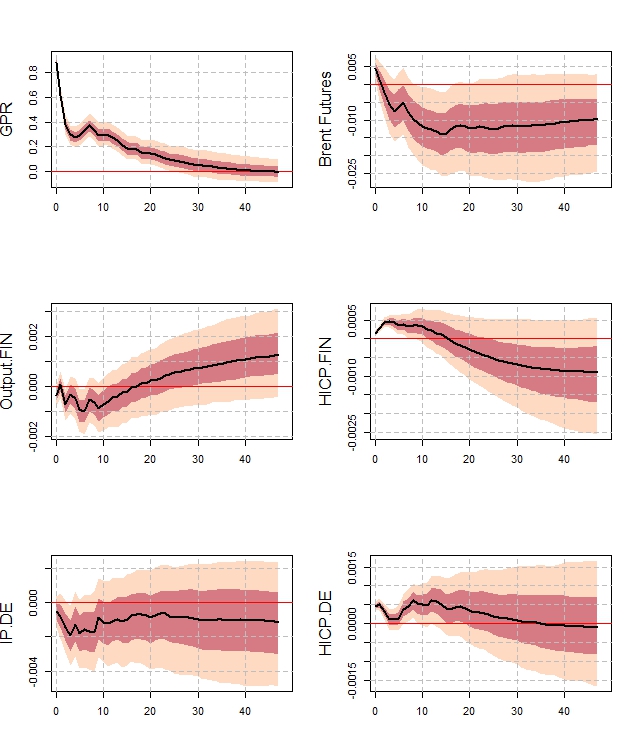

Recursive identification

Let’s start by entertaining the modelling setup that would be utilised in most papers, by identifying the error term by recursive means. In this setup with GPR at the top this corresponds to the first shock being the “geopolitical risk shock”. Below we can se some selected impulse response functions (IRFs).

According to these, at least in the short-term (within a year) the identified shock acts as an adverse supply shock. Yet, after the slightly positive impact effect, the response of Brent futures is to contract sharply. As we are concerning ourselves here with two European economies and measuring the GPR from Russian media narratives, one would assume a geopolitical shock of supply-side nature to work specifically through energy; just look at the narrative of German industry being torn by the end of cheap Russian gas and oil imports. However, these IRFs contradict these completely: German industrial production persistently goes down and consumer prices are elevated while oil futures go down implying cheaper energy. A positive energy supply shock leading to a negative industrial supply shock. This does not make sense.

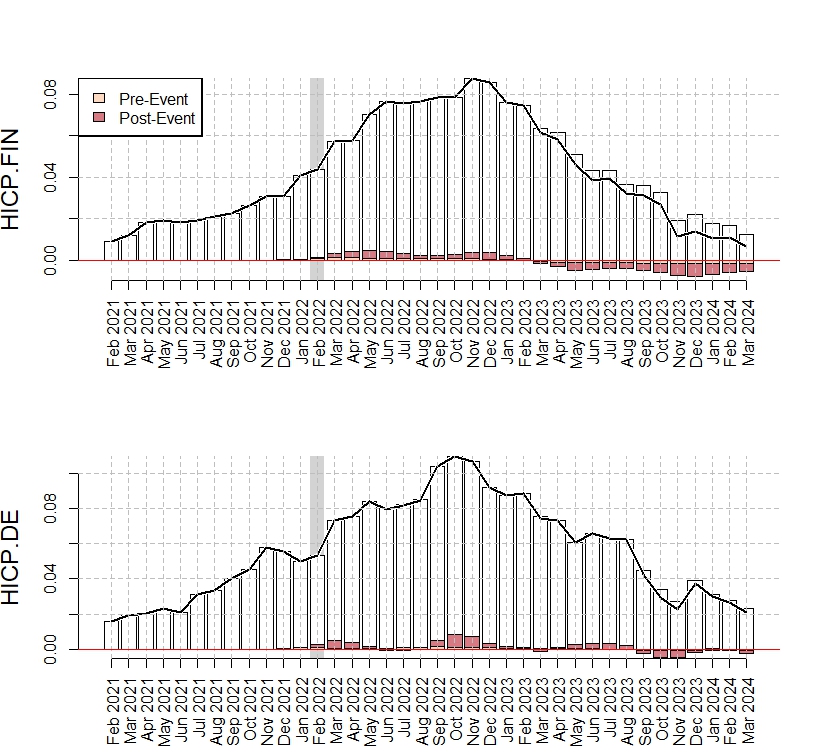

Next, let’s take a look at the estimated effect of the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022 to Finnish and German consumer prices. Anttonen and Lehmus (2025) estimated the invasion to have heightened the euro area HICP by 2pp year-on-year at its peak, while Pinchetti (2025) estimated a 0.5pp effect on US CPI. Departing from both of these, I opt to use what I call event window decompositions. Instead of tracking the cumulated contribution of shocks from the start of the sample as in regular historical decompositions, the idea is to track the cumulated effect of shocks from two distinct windows; a pre-event and a post-event window. The former is meant to capture the anticipation effects before the event while the latter is meant to capture the effects of the event realising as well as its developments after it. The pre-event window is defined to span from 2021M3 to 2022M1. Thus, it includes the first military build-up by Russia in March and April, the lull during the summer and the second build-up from November until the full-scale invasion. Post-event starts at 2022M2 and runs until the end of the sample.

As we can see, there are practically no pre-event contributions to the inflation surge. This seems highly unlikely, as both build-ups were well documented and reported by outside observers in real time (I elaborate on these developments in detail in the upcoming manuscript). The response of consumer prices is also marginal: at peak the effect on Finnish consumer prices is 0.2pp while in Germany 0.7pp. Again, this seems unlikely.

Sign and narrative restrictions

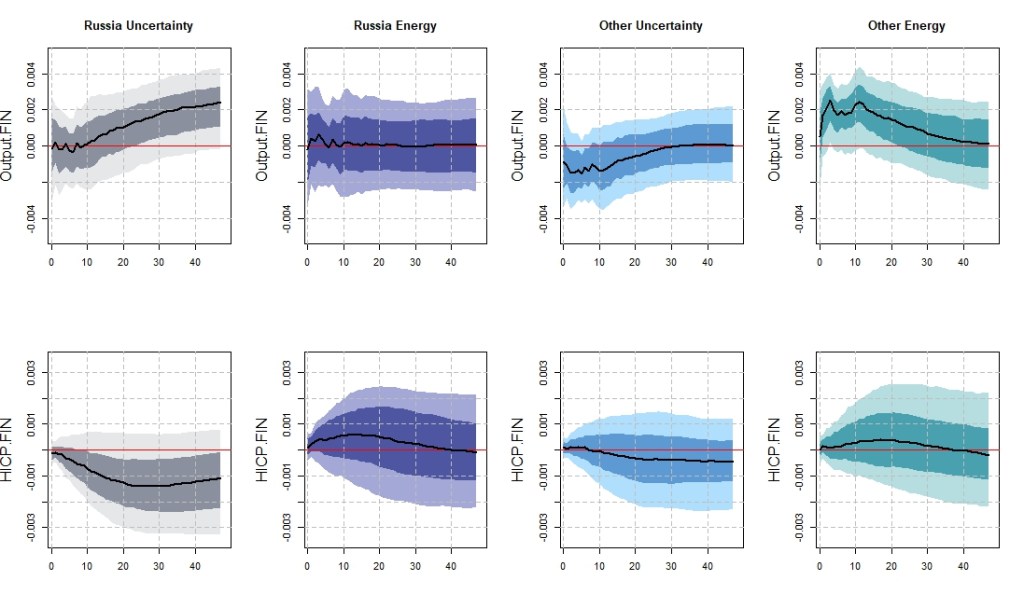

Unlike recursive schemes, sign and narrative restrictions allow us to identify several distinct transmission channels. This is key, since geopolitical events differ wildly in their macroeconomic implications. Thus, instead of events producing a “geopolitical shock” we should probably rather think of them triggering different transmission channels depending of the specifics of the event. Thus, following the idea of Pinchetti (2025), I will identify not one, not two but four shocks: two energy channel shocks and two uncertainty channel shocks. The energy channel is motivated by the fact that geopolitical event may have adverse effects on energy supply. The uncertainty channel is motivated by the fact that geopolitical events might heighten or realise the risk of outright military action which naturally creates huge uncertainties for economic activity. For both of these channels I identify two shocks: one raises the Sanction Intensity index and the other lowers it. Thus, the former should capture specifically Russian components that heighten geopolitical tensions between Russia and other countries, while the latter should capture other events. In addition, every shock is attached with a narrative restriction:

| Uncertainty Russia | Energy Russia | Uncertainty Other | Energy Other | |

| GPR Brent future Sanction | + – + | + + + | + – – | + + – |

| Largest contributor to forecast error of GPR at 2008M8 | Positive at 2022M2 | Largest contributor to forecast error of GPR at 2003M83 | Largest contributor to forecast error of Brent at 2011M2 |

As we can see below, all of the above mentioned shocks raise GPR while having different effects on Brent futures. These differences are not just of different signs but of different magnitude and persistence. This demonstrate how the discussion above about the different effects of different transmission channels is by no means trivial.

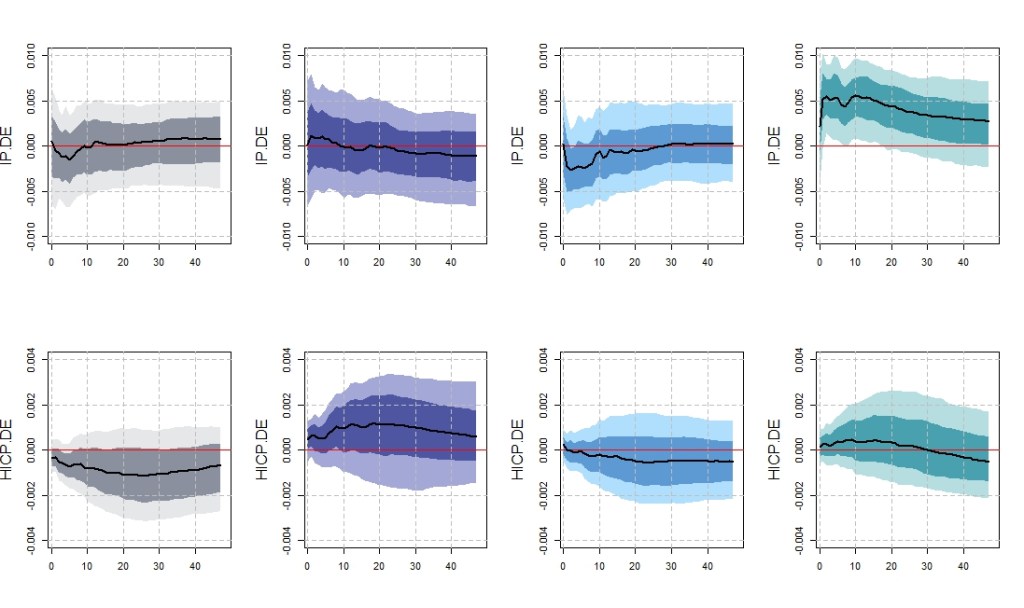

Below we can see some IRFs to Finnish and German macroeconomic variables. Again, it is clear that the responses to different kinds of GPR shocks vary in sign, magnitude and persistence. Identifying only one shock while adding additional “incredible assumptions” crams all this rich heterogeneity into a mere summary statistic. One interesting aspect is the medium-term response of Finnish output to a Russia linked uncertainty shock. This could be explained by military spending reacting to developments heightening the risk of Russian aggression. This would be in line with the lack of response in Germany, as noting the possibility of Russia as a geopolitical adversary has been much more of a tabu in public discourse.

So what about the recent inflation surge and the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine? Well, using the identification above and only following the Russia labelled shocks, the results start to look a lot more logical. The invasion of February 2022 put upward pressure to inflation through the energy channel while the uncertainty channel put downside pressure with the energy channel having the more pronounced effect. Anticipation effects from the pre-event window are also noticeable: despite Russia denying any intentions to invade to the last minute, the well-documented build-up of forces was clearly priced into the energy market. Interestingly we also have upside effects from the pre-event uncertainty channel. These are due to the lull in the summer of 2021 after Russia cooled down its first build-up.

Some thoughts

I think it fairly clear on both a priori and a posteriori grounds that identifying only one shock to describe the interplay of geopolitical developments crams huge amounts of heterogeneous dynamics into a single estimate. This is a summary statistic, not a causal estimate. While these kinds of schemes might be useful in specific situations, in most contexts the lost information on the transmission channels and their implications is arguably the most fruitful information. When facing uncertainty and the need to derive optimal actions, should we really base our decisions on estimates assuming the Iraq War, Georgian War and the Russian full-scale invasion of Ukraine having homogeneous effects on the macroeconomy? I think not.

Maybe recursive identification schemes should for the most part be retired and room be given for more credible schemes? It is not like the literature lacks them.

P.S. All coding was done in base R with the identification function taking around 12 hours to run through 1000 reduced form posterior draws.

P.P.S. I do also maintain that recursive schemes are in general (not just for GPR shocks) a bad choice that are usually motivated by ad hoc convenience, not formal consideration of the actual assumptions imposed, but that is a story for another time 🙂