As a result of the full-scale invasion of Ukraine by Russia, the prevalence of rogue states at the international stage has once again become undeniable. Besides the obvious humanitarian suffering, power politics also has macroeconomic consequences. As seen in Ukraine, fighting a war takes a huge toll on employment and human capital as working force has to be drafted to the front while physical capital such as the energy infrastructure gets relentlessly destroyed by the enemy.

Geopolitical sabre rattling comes also with more subtle consequences. For example, wars disrupt supply chains. Analysis at the Bank of Finland has shown that the full-scale invasion of Ukraine by Russia had strong supply-side disruptions to the euro area economy raising headline inflation by around 2-3 percentage points. On the other hand, the same analysis also shows that the Israel-Hamas-war in 2023-2024 had deflationary effects for the euro area economy by lowering demand.

In this post I aim to explore a more exact case of geopolitical events propagating into the broader macroeconomy, namely the case of the Finnish economy and geopolitical tensions regarding Russia. The following section deals with the the modelling strategy I am taking and is technical in nature, so feel free to skip right into results if this is not of interest.

Model description and identification

The model used here is a usual vector autoregression (VAR) identified with an external instrument. As endogenous variables I have the National Activity Index for Finland, the log-differences of the harmonized index of consumer prices ex. energy and food (Core) for Finland as well as the geopolitical risk index (GPR) for Finland. The GPR for Russia will be used as the external instrument to identify geopolitical tension shocks. Note, that the GPR for Finland is included as endogenous mainly due to the nature of the identification strategy, as instrumenting the shock requires pinning the effect of it on one of the variables resulting in partially predetermined inference on the variable in question. The model is estimated with six lags and a constant term.

In order to conduct meaningful inference, the model is bootstrapped using the proxy residual-based bootstrap of Bruns and Lütkepohl (2022) on top of a standard residual-based recursive-design bootstrap (see for example Kilian and Lütkepohl 2017, Chapter 12). Here it is conducted as follows:

- Estimate the model via OLS.

- Randomly reshuffle the reduced model errors. Simulate bootstrap realization using the OLS-estimate and the shuffled errors. Re-estimate the bootstrap using OLS on the simulated realization and save this as a bootstrap estimate. Repeat 1000 times to acquire the joint probability distribution of the reduced form parameters.

- Estimate the shock on the Step 1 reduced form model. Regress the instrument on the estimated shock to estimate the data generation process of the instrument.

- Randomly reshuffle the residuals from Step 4 to bootstrap the instrument. Randomly draw a reduced model bootstrap realization from Step 2. Rearrange the bootstrapped instrument such that the shuffled errors of Step 2 and shock identified in Step 3 stay at matching dates (otherwise the instrumentation naturally won’t work!). Identify the reduced model bootstrap realization using the bootstrapped instrument. Repeat 1000 times.

- Enjoy the whole joint probability distribution of the parameter space.

Results

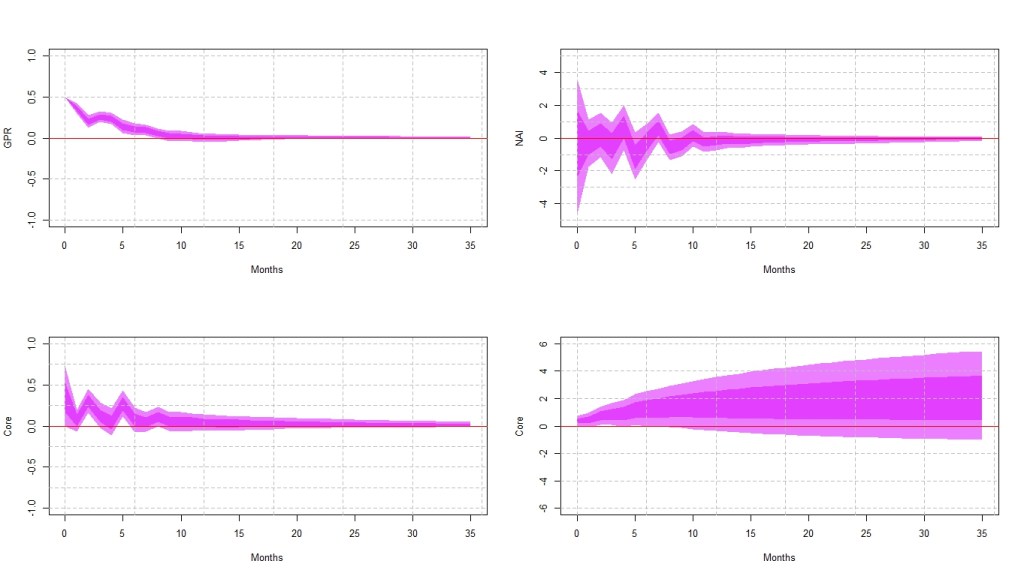

In order to have an idea on how geopolitical tensions regarding Russia propagate into the Finnish economy, let’s start by taking a look at the impulse responses of the identified shock. The shock is normalized such that it raises the Finnish GPR by 0,5 points, around which it peaked during the first couple of months of 2022. Units for the other variables are standard deviations for NAI and percentage changes for Core.

As can be seen above, the identified shock is clearly inflationary, while effect on economic activity is more indefinite. This could imply, that geopolitical tensions relating to Russia have both negative supply and positive demand effects for the Finnish economy. This could be as a result of increased defense spending and disruptions in the energy markets as well as possibly increased adversity towards investing in Finnish capital stock. It should be noted though, that the negative supply side effects seem to dominate, as most of the probability mass for NAI response is on the negative side, especially on longer horizons.

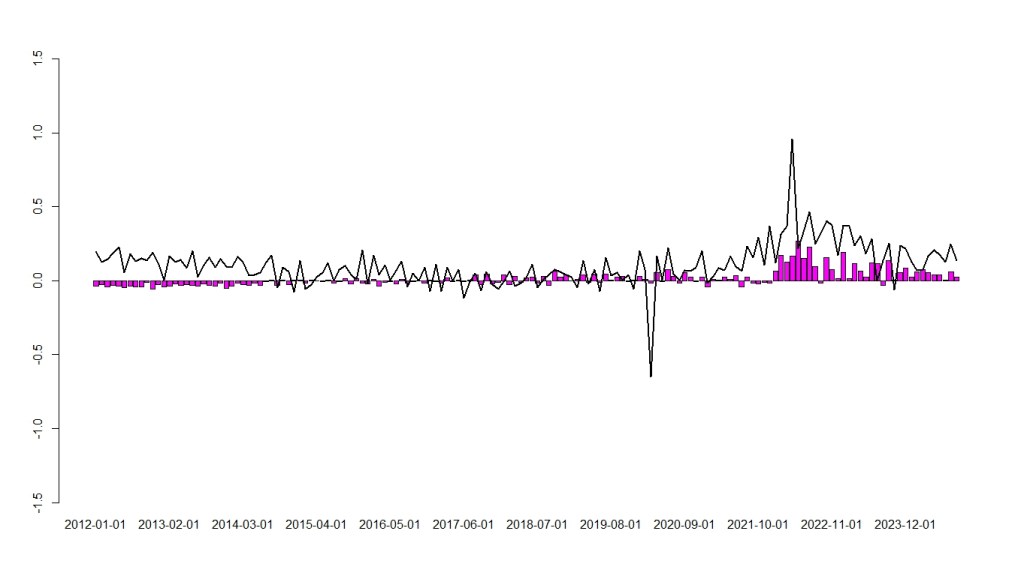

As the identified shock clearly has a clear and unambiguous effect on Finnish consumer prices, it is of interest to decompose the effect of this shock on the Core series. Below, we can see the historical decomposition of the Core from January 2020 to September 2024 using median parameter values. As we can see, from 2022 onward there has been quite significant upward pressures on Finnish consumer prices from the identified shock.